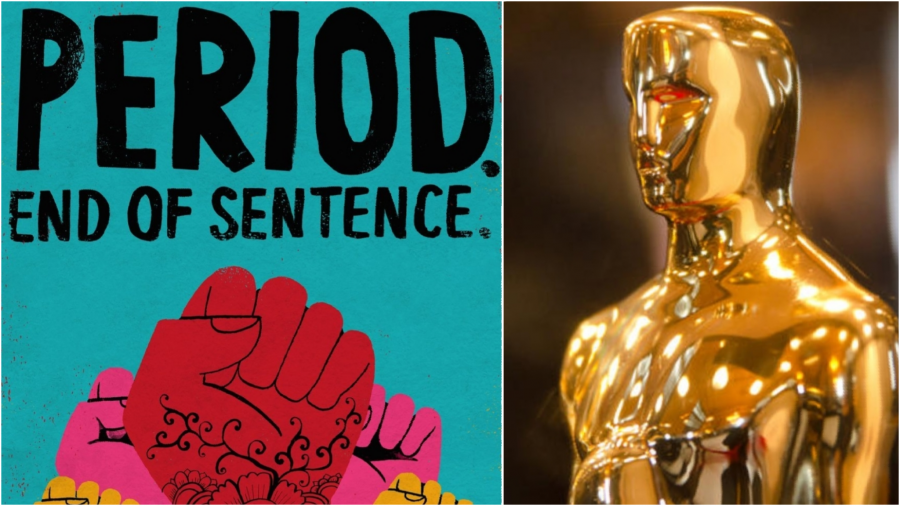

Period. End of Sentence became a surprise winner for Best Short Documentary at the Oscars this year. Aspirational, and impactful, it is centred around the taboo, and general lack of knowledge, that surrounds the natural phenomena of menstruation in rural India.

As you follow a group of women, with smiling faces and determined eyes, as they immerse themselves in the livelihood of making and selling much-needed sanitary pads across villages in India, you realise that Rayka Zehtabchi’s short directorial is much more than just a period.

Behind the lack of education and the shy attitudes towards menstruation that stays prevalent in the lives of these women, there lies brave ideologies and blooming dreams.

“The strongest creatures created by God aren’t lions, elephants, or tigers. It is a girl,” says Arunachalam Muruganantham, who revolutionised traditional attitudes toward menstruation in villages of India, halfway through the 26-minute film.

And as we are introduced to and follow along with Sneha, Rekha, Shabana and several unnamed heroes within the film, we see glimpses of this strength.

Hardworking and ambitious, these women are doing everything they can to escape the patriarchy and backward analogies that closes in and suffocates every Indian girl and women, regardless of age.

And the suffocation extends – contrary to popular belief- far beyond the boundaries of rural India. This realisation comes to me at a very early point in the film, as Sneha says “the goddess we worship is just like us. A woman. So, I don’t agree with the idea that we shouldn’t be allowed to pray while on our period.”

Her words struck a chord with me as I’m reminded of the countless times, I argued the very same point with my otherwise forward-thinking mother.

Adding to such religious shackles is the obvious taboo surrounding the subject; it is one that cannot be discussed with men. Regardless of your level of education, most often a woman shies away from the topic and a man laughs it off.

It is, therefore, the biggest step forward to see men like Arunachalam, and several others break that mould, getting involved in what is considered ‘a women-only’ issue. This lends hope that maybe every young boy can be taught to be open to understanding this perfectly natural phenomena; outside of the superficial knowledge gained from a mandatory biology lesson that most make a joke out of.

Period. End of Sentence focuses on rural areas and the issues of hygiene and affordability faced in these places. So, it becomes easy to go into a shell of denial; it can’t be happening where I live.

The film lays the foundation for much deeper issues, such as stigma, ignorance and fear, that quietly creep into and become part of our general outlook to life – no matter where you live within the vast country, and maybe even beyond.

But there is a powerful impact felt that comes out of the film that instils in me, and hopefully many others – both women and men alike- the belief that there will definitely be an end to this unnecessary, regressive sentence.

By Malvika Padin

Fantastic. Very thoughful and imaginative. Good Luck.

very well written

Nice and good post. It is very useful for me to learn and understand easily.